David Garyan: California Poets Part 9, One Poem

- Oct 25, 2023

- 14 min read

Updated: Jan 15

Spot the Author

December 22nd, 2025

California Poets: Part IX

David Garyan

One Poem

Italianarsi: An Introduction

On January 4th, 2025, at 1:07 in the afternoon, my brother and I crossed into Aosta, the 20th and last region we visited in Italy. Tucked away in the northeast corner of the country, it was, considering the place we had come to, a warm day—surprisingly sunny in terms of the season and unsurprisingly beautiful in terms of the landscape. Everything was visible.

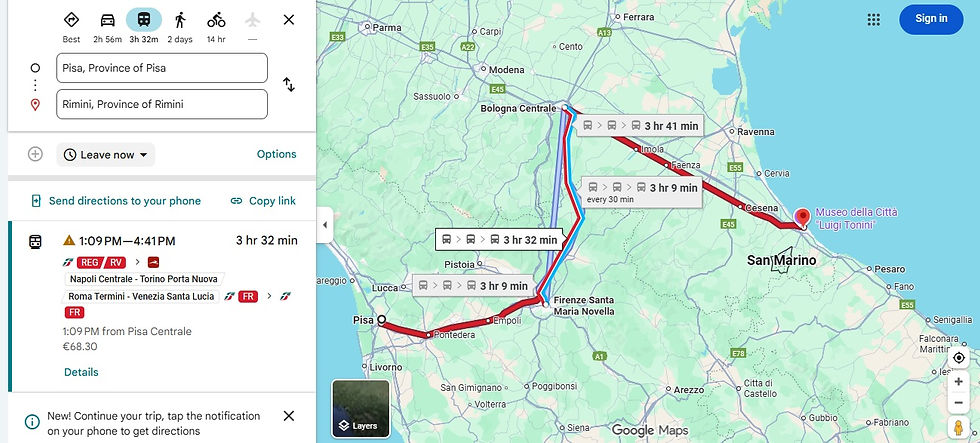

To see Italy well is not an easy enterprise. For it isn’t really the size that presents the challenge. Rather it’s the aforementioned geography, often charming and yet insurmountable, that makes a countrywide journey difficult—and this for even the best holidaymakers. Why? Well, we’re talking about a nation that isn’t wide to begin with. Except for the northernmost pockets in the east and the west, you could easily drive coast to coast in three hours. Pisa to Rimini, for instance, is a wonderful example. Not because it’s easy, but because something beautiful must be difficult (to have). And, who, in the end, is fond of doing things the easy way? Certainly not Italians. In addition, we will choose the two aforementioned cities in order to highlight the madness (scratch that, beauty, of course) that Italy’s geography possesses. They say a picture speaks a thousand words. So behold.

What would rightly have been envisioned in anybody else’s mind as simply a straight line across, is quickly complicated by the Apennine Mountains. And these must (in the name of beauty, of course) run down right between the east and west coasts. It seems neither car, nor even those cool trains in Europe can do anything to resolve the dilemma, yet even with nature’s whims, the trip from one side to the other remains just three or so hours. Oh, you’ll have to make multiple changes—there isn’t a direct line. Bellissimo.

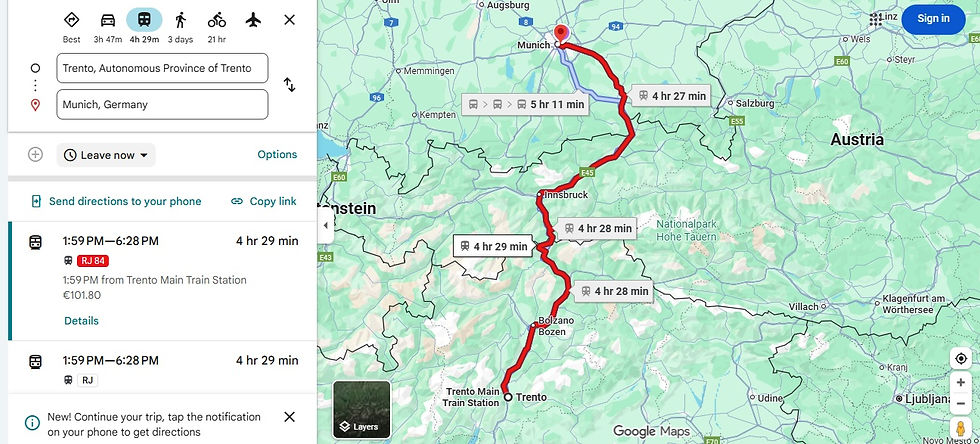

It has, by now, been readily apparent—even to the most geographically ignorant Americans—that Italy is shaped like a boot. No other country, one might argue, looks like an object that symbolizes the enhancement of human mobility (yes, walking has never been fun—yet without a pair of good shoes it’s pure torture, trust me) that, in fact, can be so difficult to get around. Just for purposes of comparison, and to further highlight the capricious nature of European geography, it would be easier to take a train from the city where I live, that is Trento, to a city called Munich, that is in Germany, a land separated from the country I live in by another country—that is Austria, and this trip would require only one train and take only an hour more than the trip from Pisa to Rimini. Behold.

Not a pretty straight line, but certainly much better. Worth mentioning is the fact that going up north likewise requires significant travel through mountainous regions, but I guess those mountains are different. What’s possible somewhere isn’t possible elsewhere.

But let’s leave travel aside and look at our beautiful boot. The pull tab rises basically level to a city called Graz, situated in Austria, and the toe, looking, at times, like it’s kicking a big rock (this we shall Sicily) reaches, in parts, further down than Tunis—yes, that Tunis, which is in Tunisia, which, if you remember, is in North Africa. Once more I’m looking at you, my fellow Americans. Alas, what is north for Africa is quite south for Italy—a nation, that, if you remember, started somewhere near a country whose official language is German. And if you want to be really pedantic about it, there are islands off the coast of Sicily, like Lampedusa, that are located below even the nation of Malta. And though my brother and I didn’t get as far down as Lampedusa, we did go to Siracusa, which is basically level to Tunis.

Johann Wolfgang van Goethe once remarked in his 1817 travel diary, Italian Journey, that “Italy without Sicily leaves no image in the soul: for Sicily is the key to everything.” Well, try getting there first. The soul, whether it’s a country’s or an individual’s, seems, always, to be the most remote thing a person can grasp. But in Goethe’s day they did. And what they tried to fathom, most of all, is the essence of Italy.

The Grand Tour, as it was known between the 17th and 19th centuries, was a traditional aristocratic custom of embarking upon a long journey throughout Europe, with Italy as the principal destination—usually upon reaching the age of twenty-one. It was a sort of rite of passage, masquerading under the guise of education, to acquaint the crispiest of all upper-crusts of European society to the origins and glory from which their celebrated continent had been born. Say what you will about the uppitiness of the enterprise, along with that segment of society in general, but the nobility of that time believed in something that we, as practical culture, seem to have lost—that the education of the streets is as important as the education one receives in the hallowed halls of university, or from incredibly uppity tutors with strange, sophisticated hair, as was the custom in those much more refined days. A paradox one might say, but so it goes, according, at least, to the Tralfamadorians, especially if the death of a custom can be faced with the same apathy as the death of a person. And Goethe, along with his peers, is certainly dead, as are the traditions encapsulating the Grand Tour, but here he is anyways in all his infinite, all-too-Italian glory.

In no way shape or form, however, was any demise of a person, much less the passing away of a single tradition going to deter my brother and I from thinking ourselves not only old enough to travel, but likewise enlightened aristocrats, ready to discover the marvels of Europe. And so we spent roughly five years going about one single country for various reasons, probably much different from the ones that Goethe had at the time. When we landed in Milan on September 4th, 2019, it was, apart from a short layover two years ago in Rome, our very first time here. That was also the last time we saw the US. Anyone familiar with European law knows the American passport gets you little in these parts. You can’t just show up and stay as long as you want. Who do you think you are? An aristocrat? Either you study in this old land, in which case authorities will (kindly you’ll hope) issue a stay permit you can renew every year (for as long you study, my privileged boy), or you fill a role in some critical sector like medicine in which there’s shortage—otherwise you’re out of luck. If, however, you don’t have enough luck, but you’re lucky enough to have deep pockets, you may choose to pump a ton of money into a startup and that, as well, will confer upon you the hallowed right of residence. These, my friend, are the only options—apart from marrying an Italian woman or man. Just, alas, when all hope had been lost, it was the digital nomad visa—introduced very recently—which has has come to save the day, and which, these days, seems to be the choice of expediency (for romance can be short and intense, but it should never be long and expedient, at least if you ask people in these parts). And so going that aforementioned route you'll have to make enough money on a laptop to satisfy the Questura (that’s Italian for police station, young squire). Why that? Because it’s the Questura that processes all documents for the residence permits, regardless of the reasons for which you’re getting them.

With rampant backlogs and endless paperwork to be done, the process takes a long time, and the applicant cannot travel to another European country while the application or renewal procedure is ongoing. Yes, you can journey anywhere else, but not throughout the continent. This, naturally, was not the main reason why we chose to de-emphasize international vacations, but it was nevertheless a deciding factor for why have seen more of Italy than the average Italian. And what is it that we have learned? Well, that the place we’ve called home for six years now can really be described with one word: contradictory.

To understand Italy is to realize that there’s in fact no such thing. While the country that was unified and then subsequently created in 1861 does indeed exist, there isn’t much else, apart from the language (which in and of itself is nothing more than a refined Florentine dialect now spoken by an overwhelming majority of the country) that unites Italian, and even then it does a poor job because of how differently that Italian is spoken across regions. Perhaps what makes up the best indicator of national unity occurs during the World Cup and Euro championships, when all “Italians” unite under one banner and cheer for a singular cause. Other than that, it’s campanilismo all the way to the bank, which just means people have closer connections to the regions they come from rather than some national construction that, less than two-hundred years ago, was imposed by the region of Piedmont, and this through the conquests of Giuseppe Garibaldi, onto the whole region, which had been ruled by the Austrians, the French, the Spanish, and the Vatican—all entities who left their mark on what is today called “Italy,” but nobody can really tell you what that is. In fact, the region my brother and I live in—Trentino/Alto-Adige—wasn't even a part of Italia until the early 20th century, in 1919, when Austria, after being defeated in WWI, ceded the territory to its all-too-happy neighbor. There are, thus, large communities, especially in Alto-Adige, who remained within these borders that don’t even consider themselves Italian, even if they might speak the language, and they, I can tell you for certain, are anything but happy about it. For many in these parts, the first language they learn is German, which already should tell you a lot, but if it hasn’t, consider this: Their food is different, their culture is different, and so too their mindset, which is why the government has granted the region autonomous status to keep it from seceding. And there isn’t just one autonomous place—there are five, all with distinct languages, cultures, and traditions that, at best complicate, and at worst defy, what it means to be Italian. And while the history of the remaining fifteen regions may not be so drastic, it’s also not that far removed from those realities.

It may hence be more correct to say that in these six years of living here, we, in fact, did not visit twenty regions in one country, but twenty countries in one region. For when we crossed into Aosta, the final one we had to see (yet another from the autonomous bunch), we saw a culture that was more bonjour than buongiorno, with tourist plaques and even street names often written first in the former language, instead of the latter. Not only, thus, did the geographical closeness to France play a part, but really it was the cultural proximity that was so easy to feel—for even if our host country is shaped like a boot, it was nevertheless a long walk from Aosta to the French side of Mont Blanc. The atmosphere, however, inside what was still politically Italy—but culturally remained outside it all—had said enough. The same is true for many places in Alto-Adige.

There’s this joke—not quite a joke because it was kind of true in the past—that before the country was unified, a banker from Milan and an aristocrat from Sicily had to speak French to understand each other. The description of Italian dialects as “dialects” is really a misnomer and does much to distort the perception of how different these so-called dialects are from the “standard” Italian, which, as has already been stated, is merely a refinement of one regional tongue—the Florentine one. And why that particular regionalism? Well, the way Chaucer’s literary influence standardized English in England before French was spoken there, so did Dante’s, Petrarch’s, and Boccaccio’s widespread recognition similarly shape what would be spoken in this newly-formed country. But it may not even be that. Unlike French, which was consolidated through literature, solidifying the Francien dialect as the foundation for the national standard, there are arguments that Italian wasn’t actually assimilated until the advent of television—in the mid-twentieth century.

But enough aristocratic blabbering about language. Let’s finally dive deeper into the actual travels we did. Take, for example, two cities like Perugia and Pescara. The fact that they start with a “p” is purely coincidental, yet that is about as much as they have in common. The former is a city on a hill, so beautifully preserved with Etruscan architecture, that walking through gives you the sense of having stepped back into time. Throw Italian patriotism and obsessive preservation of history into the mix, and you start to wonder about one thing: Hundreds of years from now, when some of those buildings can no longer be renovated, how will Perugia embrace modernity? The latter city, Pescara, one might say, was spared from that fate. Heavily bombed during WWII and basically brought to total destruction, the city was for all intents and purposes rebuilt from the ground up. Fortunately, the birth house of poet Gabriele D’Annunzio still exists and apart from the Church of the Sacred Heart that stands in the center, nothing else is particularly historical-looking in the rest of the city. Pescara, thus, may not be as significant from the perspective of the past, but it will have far less problems accepting the future, unlike Perugia, for instance, where the buildings cannot simply be raised for something new to be built in their place. That fortune, or plight (call it whatever you want to), is representative of the bigger difference between the US and Europe. The latter is a continent, to some extent burdened by the past, while the former is a country too often obsessed by creative destruction. Shops seem to pop up and close overnight—without much hindsight or foresight. Buildings are demolished and, without great deals of nostalgia, new things rebuilt, so much so that you may leave a certain place for three months and come back to see it radically altered. Such changes in Europe take years, if not centuries, for better or worse. The lack of a history gives one more freedom to destroy what they’ve done—the freedom to start something anew without looking too long(ingly) in the rearview. This is what has created America’s dynamism. Go forward and never look back. Yet the absence of a concrete center upon which to fall back on has now caused it to spiral out of control, in ways that Europe, after its near-total destruction, won’t do again. The need to preserve history on a much “older” (yet admittedly more stubborn, obstinate, territorial, traditional, and at times, even backward) continent is a bulwark against what America is suffering as a result of its uncentered dynamism.

Let’s return to the contradictory nature of Italy. To understand a person would really have to live here—to brush up against its worst forms of bureaucracy, and then experience the kindest displays of generosity. To deal with the most impatient technocrats, and then drink Aperol Spritz with the easiest-going of friends. To experience all-too-familiar narrow-mindedness and judgement from die-hard traditionalists/conformists, and then live amongst citizens who’ll forgive most of your mistakes. To live in isolation and to be misunderstood, and then to be asked where you’re from and what it’s like there out of honest curiosity. This is Italy, and it really doesn’t matter whether it’s the north or the south; that construction, as my brother and I have come to found out, is itself more fiction than fact—a post-unification narrative promoted by the people, who, themselves, did the unifying to justify their superior positions when, in truth, it’s the south which remains more interesting, with a more ancient history, and certainly better climate. According to a University of Bocconi website, it was precisely during the early modern period that “the Kingdom of Naples was one of the largest and most economically significant states in pre-unification Italy. Ruled successively by Angevins, Aragonese, Spanish Habsburgs, and eventually the Bourbons, the region was notable for its agriculture-based economy, feudal structures, and heavy taxation. The kingdom’s economic policies played a crucial role in shaping the distribution of wealth and income.” Sounds to me like the European welfare state. The south may be economically poorer today, but what it lacks in finances it makes up for in the more approachable people, better food, and more vibrant culture. What can’t be denied, however, are the contradictions inherent in every part of society—that, along with the language—might in the end be what unifies Italy.

You may find yourself in the north, and you may find yourself in the south, and in both places come across people who are afraid of sitting in air conditioned rooms, yet have no problem with sitting outside a café breathing in smoke—and perhaps even smoking themselves. You’ll find doctors who smoke outside hospitals and then go into them to say you need to lose weight. You’ll find people driving electric cars to save the environment, all while taking a puff at a red light. You’ll find kids smoking outside of schools with no concern from the staff, while crosses hang in the classrooms. You’ll find parents who wrap their children in countless layers to make sure they don’t catch a cold—all the while lighting one up in some playground. This is Italy. You have no idea how many people we've seen pushing strollers with cigarettes in hand. Contradictions like these exist in every part of society—north, south, east, west, and everything in between. But let the poem say more about that .... Well, one more thing about the title. “Italianarsi” is a portmanteau of “Italian” and the Italian reflexive pronoun “si,” which can be translated as “Italianize yourself.” So get to it, young squire.

Italianarsi

In Italy we walk slow. Then we talk fast. And we drive fast. Then we live slow. And that with good people. Yet with bad leaders too. Such warm generosity. And bureaucracy slew.

We really like honesty—so won’t you be frank? But keep bella figura—the real you will tank. And should you be late, know that we’re flexible. But after-lunch cappuccinos? You can’t be Italian!

You make mistakes? Of course we forgive them. Chicken on pasta? No forgiveness—of course.

Be relaxed, be informal. Yet also watch out: Age and status are watching. On buses the young give their seats to the old. In life they leave just the land to find jobs.

Expats arrive: They see family values. Locals take flight: Driven by nepotism away. And yes there’s deceit. But what’s that again? Just the lie not to harm any feelings.

Such masters of romance. Whose birthrates are falling. Such lovers of family. With the lowest birthrates in Europe.

Be kind—say permesso when passing. Be passive—form queues how you want.

And what about culture? Foster it now. And innovate too. Now wait a minute: Don’t change tradition—that’s too askew.

Going out with wet hair? Colpo d’aria. Smoking near your kids? Outside it’s okay.

We’re open: Who are you? We’re curious: Who are you? Either way don’t forget: When invited to dinner, leave the strange food at home. And moderate drinking. But don’t share your pizza.

Wait. We’re not done here. There’s yet one rule to own: Never break your spaghetti—even alone.

It seems you’ve learned well. Well also know this: We do what we like. All else remains Swiss. To cross empty streets? Don’t wait for the green. Solo at stop signs? Don’t stop just to glean. (Some laws are meant to be broken.)

Italians are gentle, Italians are kind—Italians have Room Zero and 41-bis.

The driving stays fast—no time to let strangers cross. But time’s always plenty when staring at strangers.

Homes are especially clean, locals well-dressed—you’ll find both on streets well neglected.

There’s campanilismo—pride for one’s town—yet dialects are dying ... it’s discouraged to speak them.

And so if you come to Italy, you’ll love it at once, but once time has passed, all love gets tough.

Appendix

It would be helpful to add a visual element to the prose that personalizes the text a bit more. Here are, thus, a couple pictures from each region. These were selected not with the intention to impress, but rather to demonstrate the joys of travel and to try and catch some of the quirky aspects of each place, for every destination is more or less the same—they just have different looking squirrels, as one SNL skit once pointed out.

The pictures above are listed below in alphabetical order (two photos for every region in bold). The astute observer will recognize the reasoning behind some of the selections. My brother and I tried our best to visit more than one city, though logistically it wasn't always possible. This is more or less a breakdown of where we went. Memory gets a bit foggy after five years, so excuse any possible omissions. In any case, there should be at least fifty.

Abruzzo: Pescara

Aosta Valley: Aosta

Basilicata: Matera

Calabria: Reggio Calabria

Campania: Naples, Pompeii

Emilia Romagna: Ravenna, Rimini, Bologna, Forli, Comacchio, Modena, Russi

Friuli-Venezia Giulia: Trieste, Duino

Lazio: Rome

Liguria: Genoa

Lombardy: Milan, Monza, Desenzano, Sirmione, Busto Arsizio, Mantua

Marche: Ancona, Recanati, Porto Recanati

Molise: Campobasso, Termoli

Piedmont: Turin

Sardinia: Cagliari, Olbia

Sicily: Messina, Cefalu, Palermo, Catania, Syracuse, Aci Castello, Aci Trezza, Aci Bonaccorsi

Trentino-Alto Adige: Trento, Bolzano, Riva, Pergine, Rovereto, Levico, Caldonazzo, Pietralba, Aldeno, Lavis, Mezzolombardo, Merano, Mattarello, Andalo, Bondone

Tuscany: Florence, Sant'Andrea in Percussina

Umbria: Perugia, Assisi

Veneto: Verona, Padua, Venice, Mestre

Comments