“Quarantine Diaries,” by David Garyan (Day 17)

- Nov 22, 2023

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 24, 2025

Quarantine Diaries – Day 17 March 31st, 2020

Trento, Italy

Games

As I was writing yesterday’s entry about the possibility of freedoms being eroded under the guise of the coronavirus, this was developing. I guess Hungary is a dictatorship now: The parliament is suspended; journalists can be punished for “inaccurate” reporting of the coronavirus; and there’ll be heavier penalties for violating quarantine laws; these are just some of the measures, according to CNN.

On the national Hungarian radio, Kossuth, Viktor Orbán declared the following: “We cannot react quickly if there are debates and lengthy legislative and lawmaking procedures. And in times of crisis and epidemic, the ability to respond rapidly can save lives.” Speed and efficiency have always been emblematic features of dictatorships. Perhaps, in the spirit of containing the coronavirus, Hungary too is operating on these mathematical principles.

Maybe someone needs to remind Prime Minister Orbán that the wonderful idea to fix problems quickly and efficiently has already been taken up by the most ruthless dictators, including Stalin; his fear of falling behind the industrialized West led him to proclaim the following in 1931: “We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make up this gap in ten years. Either we do it or they will crush us.” Well, he did do it, and many of the five-year plans were met in four years, but instead of avoiding being crushed by the developed world, Stalin crushed his own populace to achieve industrialization.

In all fairness, according to data in David R. Stone’s article, “The First Five-Year Plan and the Geography of Soviet Defence Industry,” Stalin’s industrialization did prepare the country to some extent for WWII; in that sense, like Stalin, Orbán too will probably use his authoritarian privileges to achieve good results for Hungary in terms of containing the coronavirus, but at what cost to his people?

Just to shower some more needless praise on dictators, in her book, “Stalin’s Apologist,” Sally J. Taylor argues that Walter Duranty, whom she described “as the No. 1 Soviet apologist in the United States,” was a key figure in getting Roosevelt to recognize the Soviet Union in 1933. His coverage of the five-year plan contributed greatly in getting FDR to pronounce his decision in 1933. Duranty won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting, which, according to Taylor played a big “part in helping to achieve US recognition.” Later, the New York Times called his denial of Holodomor “some of the worst reporting to appear in this newspaper.”

Another relevant story developing last night was the growing concern about UK police officers “overreaching” to enforce the coronavirus lockdown. Some so-called democracies will be slower in adopting authoritarian policies than others, but if things do indeed get really bad, no free country (to save its own ass) will able to resist the temptation of fixing problems quickly—all for the good of their citizenry’s asses, of course. Naturally, all this is quite relevant, but it’s best not to repeat the same thing over and over. I’ve made my case and these recent events have only confirmed my suspicion about the direction in which this pandemic is taking us.

Let’s forget the future (along with the past) and focus on the present. My brother and I took one of our late-night walks very early at night today, not returning home until about half-past one in the morning. We’ve done this a few times already and never saw anyone else; this time, however, we saw a crowd of two. I wonder what the situation will be like in a few weeks when more people will decide they’ve had enough. We reached the banks of the Adige, and my brother took this picture.

Ah, beautiful, it’s a sign which tells us where walking is permitted. It’s comforting to know that signs still aren’t digital; they’re sort of the physical embodiment of someone’s availability—at least how it used to look like in the past.

Ever since the advent of conventional telephones, people have been more available, but if you’re not home—you’re not there. Cell phones came around and put a longer leash on people—you’re now at home regardless of where you are. Finally, the internet came around and gave everyone a home (page). Here’s the University of Bologna founded by Toshiba in 1088—just look at how beautiful the campus is.

I don’t know—am I really losing it? Didn’t I mention signs somewhere? Yes, I did—the sign which permits walking in a quarantine; technology hasn’t poisoned that yet; however, the way telephones have infringed on our right to be unavailable, the age of digital signs will likewise arrive soon. Everyone will finally know what they mustn’t do 100 percent of the time and no one will be able to say: I didn’t know, or I wasn’t available, or there was no sign. Indeed, signs were already becoming a problem in 1971, when the Five Man Electrical Band sang: “Signs, signs, everywhere signs.” Just wait until technology takes over that arena as well.

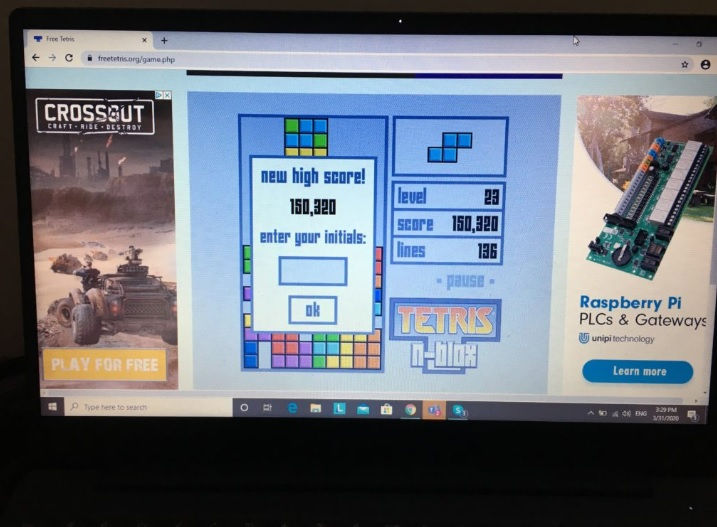

Well, what else happened today? Ah, yes, my brother played Tetris and got a high score of 150,320; this particular game was played on the University of Trento, Lenovo Campus because that’s where my brother goes to (virtual) school. Just look at that beautiful campus, but more importantly, focus on the score. I can barely manage to get 10,000; this really shows how bored he’s become.

Tetris is an evil game; according to the US, it’s a communist plot to overthrow the US. Did you clink on the link to verify my facts? You should; it took me a long time to find the evidence and the research is peer-reviewed. It’s obvious that no one clicks on the links, but this one’s worth your time. Trust me.

Tetris was invented by a Soviet engineer named Alexey Pajitnov. Ah, dear reader. Despite what I said, I was hoping you wouldn’t click on the link; yes, you can bet your ass I’m laughing at you. Indeed, Tetris really was invented by the Soviets, but, much to the dismay of the US, it’s not a communist plot to overthrow the US. Sorry to disappoint everyone, but as I’ve said many times: I’m going to do that often.

All this doesn’t change the fact that Tetris is a frustrating game because there’s no victory and there’s not even an end to it. No, USA, you can’t declare war on Tetris and win—the best you can get is an infinite conflict, but given how pleasing war is to you, that scenario would probably be better.

Indeed, to be a Tetris player, one must be a lifelong student, one must relinquish the ego, and one must abandon the pursuit of power, among other things. People today are much too concerned with meeting objectives, goals, dreams, winning—whatever you want to call it; they do everything possible to realize that final aim of hitting the target and finishing the game. Done—I’m the winner in the world of finite games.

However, there’s another game that we rarely play in life—the infinite game—which according to James Carse isn’t played to achieve victory, but “for the purpose of continuing the play.” Infinite games, thus, according to Carse, aren’t concerned with the trivial aspects inherent to politics, sports, and war. As he states: “The infinite game—there is only one—includes any authentic interaction, from touching to culture, that changes rules, plays with boundaries and exists solely for the purpose of continuing the game. A finite player seeks power; the infinite one displays self-sufficient strength. Finite games are theatrical, necessitating an audience; infinite ones are dramatic, involving participants.” Basically, what all this means is that there aren’t enough Tetris lovers in the world.

As we’ve already established, we definitely know the US isn’t playing Pajitnov’s famous game, and not because it was invented by Pajitnov—a Soviet—but because there are no winners or losers, which is funny because Tetris was and continues to be very popular in the US.

About the US’s love for finite games, Vinay Lal writes: “Though the protocols of supposed sportsmanship require an acknowledgement of the heroic efforts of the loser, the culture of American sports demands that there be clear winners and losers. Nothing is as dreadful as ambiguity: the evil is out there, and one must be either for Osama bin Laden or for [sic] him, just as one cannot be both for and against America.” Yeah, that seems about right.

Even education, according to Lal, is a finite game symbolized by the hallowed rules of final projects, grades, and ultimately diplomas; that’s what I mean by the US not enjoying Tetris. In all fairness, a lot of people no longer play it, despite its popularity.

Consider this scenario: You’re a college freshman being offered the opportunity to buy a diploma or to spend four years getting it; both options are legal and no one will know how you graduated—employers can’t ask either; in the first case you’ll have missed a chance to learn something. Again, both choices are completely legal; which one would you choose?

The grading system of Harvey Mansfield, a professor at Harvard, might give a clue as to which choice people are more likely to make. Many students know him as “Harvey C—” because he gives students two grades—the first mark is the one they actually deserve and the second is the one which he’ll actually enter into the system. Many students end up not caring what their “real” grade is, just as long as he enters the higher grade into the system. Is education an infinite game, or what?

Here’s an aerial view of me at the University of Bologna, Toshiba Campus, playing the finite game of getting my diploma while not giving a shit about classes, really. Gone are the days when Greek academies used to impart holistic education from the mouths of peripatetic philosophers who would accompany their students around agoras, speaking of wisdom after wrestling practice. What diplomas? What graduation? Ah, the days of infinite education. Just look at me in the finite game—trying to impress the professor and get all my participation in for the day. Something’s definitely been lost.

I recall now the words of Arthur Rimbaud from A Season in Hell: “Does this farce have no end? My innocence is enough to make me cry. Life is the farce we all must play.” I know, Arthur. I know. You would never have accepted this humiliation.

All the way from quarantined Italy: I may seem crazy now, but in a month everyone here will be no different.

Until next time.

Comments